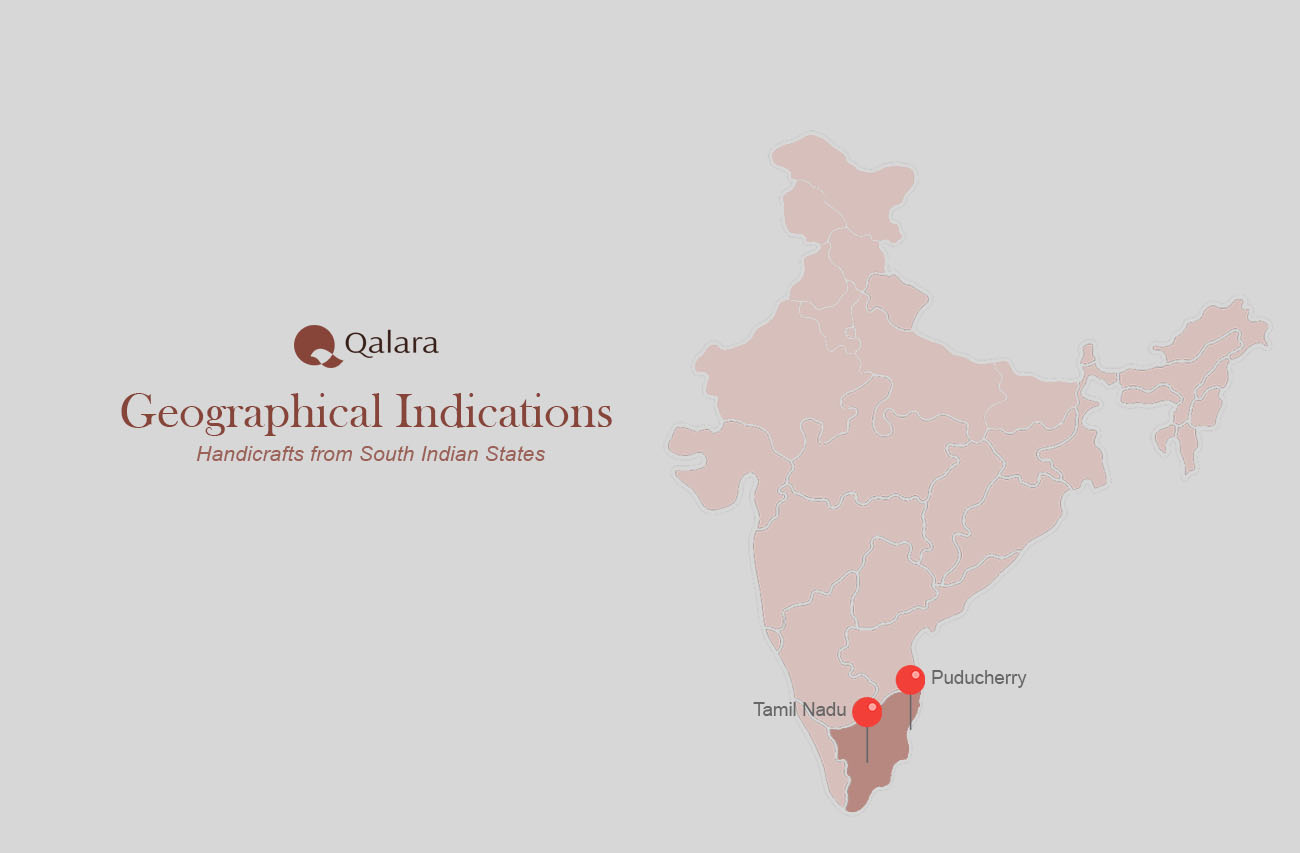

Crafting legacy: GI handicrafts from South India (III)

fter a long journey from Andhra Pradesh and Telangana into Karnataka and Kerala, we have finally arrived in the stunning landscape of Tamil Nadu and its neighboring regions. In this third and final installment of our series on GI handicrafts from South India, we are excited to present the rich artisanal traditions of Tamil Nadu and the union territory of Pondicherry!

This article will delve into the heritage crafts of these regions, showcasing those that have earned the prestigious title of GI handicrafts.

Puducherry

Popular GI handicrafts

⬝ Tirukanur papier mache craft

GI issued on 18th August, 2011

Origins: Papier mache of the Thirukannur town in Pondicherry evolved into its kind of craft variation around the 19th century. Pondicherry was one of the few French colonies in India even during the prevalent British Raj era in the rest of the country. This brought a lot of foreign culture to the land that the locals adapted around and rendered a new variation that was a beautiful fusion between these two worlds. One such rendition happened when the French introduced the craft of papier mache.

Among all the clusters of craftsmen, the artisans of Thikannur effortlessly merged this foreign technique in their local designs, introducing this new craft.

Traditional usage: The papier mache craft is extensively used for making decoratives, toys, and showpieces. Thikannur’s products included similar pieces in an Indian context. These were novelty idols of deities, rural men & women, animals, decorative masks, and so on.

Every kind of product is even colored differently here based on a palette that the artisans believed apt. Religious idols and related decoratives were colored orange and rose pink while figurines of weddings and newly wedded couples were colored orange and pink. White, pale blue, or cream colors were used for toys.

Contemporary influence: Currently, it is not a widely practiced craft and relies a lot on its rich heritage of being one of the oldest craft forms in the country. Multiple organizations helped retain its relevance by giving it a GI tag and patronizing the crafting communities.

Crafting method: The method starts with mixing a coarse paper pulp with limestone, copper sulfate, and rice flour to form a paste. Earlier this was made with glue made from tamarind seeds, paper powder, and lime powder.

This paste is molded into the desired shape of the product which is drawn, designed, and detailed by artisans. Lacquer is used on the figurine to give it a bright and vibrant color which completes the process. Once it is left to dry, the product is ready.

Raw materials: Coarse paper pulp mixed with copper sulfate, limestone, and rice flour is a unique pulp mix that gives it a different kind of sturdiness and visual aesthetic. This mix is also a key differentiator of the Thirukannur variation from the other kinds of papier mache crafts.

⬝ Villianur terracotta works

GI issued on 18th August, 2011

Origins: The terracotta work in the small commune of Villianur was initially practiced by the craftsmen of the ‘kulalar’ community. The origin of this craft is subject to high debate but it is agreed that it is almost as old as 20 generations of artisans.

There is some argumentative evidence of finding terracotta works in an excavation site called ‘Arikamedu’ whose archeological history can be linked to 1st century Rome. Amongst all these speculations of where this comes from, now this terracotta works belong to Villianur and its talented artisans.

Traditional usage: Terracotta work predominantly revolved around modeling figurines. This craft is also the same. Idols, statues, and other such figurines are the primary work of this craft. The designs include deities, animals, rural life, and other customized orders.

Contemporary influence: A major effort towards maintaining the relevance of this craft was made by Mr. V.K Munaswamy, one of the craftsmen from Villianur. He set up a special training system for the craft which is now attended by national and international students. His effort to conserve his loving art has been recognized by various institutions including UNESCO which facilitated his institute with more than 68 awards.

Crafting method: The clay mixture used for the craft is first ‘sifted’ to remove all the hard rocks in it which might affect the product’s finish. It is then kneaded properly to form a mixture ready to work with. The mixture is first dried for a while and then used in small quantities to mold designs and figurines accordingly.

The body parts of extremely large statues are molded separately and joined together later. Once the complete figurine is put together, it needs to be dried for 12 hours after which the product will be ready to sell. The products made with this terracotta mixture range from a size of just an inch to over 6 feet!

Raw materials: The clay mixture used to make the figurines is the main differentiator in Villianur’s terracotta works. The composition is 20% green clay, 40% fine sand, and 40% thennal. The tools used for crafting this clay mixture are completely made of bamboo.

Tamil Nadu

Popular GI handicrafts

⬝ Toda embroidery

GI issued on 4th March, 2013

Origins: This unique style of fabric embroidery belongs to the Dravidian ethnic group, the Todas. Todas live in the Nilgiri hills region in Tamil Nadu and have a population of 1500, spread across multiple hamlet settlements. Cut off from the metropolitan hustle-bustle, this is a community where farming is the most prevalent occupation. They worship cattle and lead a very fundamental lifestyle close to nature.

While the men worked, the women took up embroidery work as a vocation. But with a unique design aesthetic and features like reversible wear and fine weave texture, it emerged into a fascinating art form celebrated by others as well.

Traditional usage: Toda embroidery initially was done on shawls since it was more used as an add-on piece of clothing in hilly areas. The embroidery is done on white cotton cloth, using red and black threads. All the designs follow this color palette. The embroidery would be so fine and precise that it would be often mistaken for woven cloth instead of an external design. The work is also such that the cloth can be worn on both sides.

The design themes are rarely documented and are mostly dependent on the creativity of the women and the inspiration they take from the nature around them. So, the design predominantly includes celestial bodies like the sun & moon, reptiles, animals, cattle, rabbit ears, and buffalo horns.

Contemporary influence: Embroidery is today used on a lot more accessories like sarees, kurtas, jackets, skirts, pajamas, tablecloths, and so on. Toda embroidery found lots of takers across the country. But, reduced interest in the younger generation to continue the craft also means that the future looks unpredictable. Along with this, it hasn’t fully been introduced to the global market.

Multiple organizations and stakeholders have been trying to help the craft with rebranding, designing, and taking it to the international stage as a rural craft form representing woman empowerment.

Crafting method: This embroidery is a very precise craft that is done by counting the weft and warps. Traditionally, the designs were laid in ribbons around the fabric, with each ribbon being apart by six inches. The work is so intricate that the end design looks like a fine woven cloth.

Raw materials: The embroidery can be done using threads of cotton, or wool traditionally. But working with any other fabric is possible too.

⬝ Thanjavur doll

GI issued on 9th September, 2008

Origins: The iconic bobblehead Thanjavur dolls were first crafted in the 19th century when the Thanjavur region was ruled by the Maratha king, Saraboji. It is said that his love for art and color pushed the craftsmen to come up with new kinds of figurines that would pique his interest. The Thanjavur doll is what they finally landed on.

Traditional usage: The kinds of Thanjavur dolls are mainly bobbleheads and roly-poly toys. While being perfect as play toys, they are great as showpieces and show a lot of Tamil Nadu’s folk culture in their designs. These include royal figures, deities, and dancing characters from traditional art forms.

Contemporary influence: These dolls remain in steady demand from Indians and international buyers. The issue however lies with the shortage of labor. Younger generations in the families would gradually gravitate to other appealing jobs instead of the handiwork of dollmaking. Many families have also changed jobs along the way.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, the community saw its biggest labor crunch. While different organizations have been helping with conducting training sessions for the younger generations, the turn-up is low and could only be tracked over more time.

Crafting method: The body of the dolls is made using a lightweight dough that is a mixture of tapioca flour, papier mache, and plaster of Paris. The dough is split into two halves and molded according to the design. The halves are dried and joined together with an adhesive. The feet form the pedestal which is heavier and made from clay. This method majorly applies to roly-poly and bobblehead toys.

Raw materials: Earlier, terracotta was used to make the body of the doll which was later replaced by the papier mache and tapioca flour dough because they are lighter.

⬝ Swamimalai bronze icons

GI issued on 31st March, 2016

Origins: The bronze icons here are sacred idols of Hindu deities, crafted by the ‘Sthapathis’ tribe of the Swamimalai village in Kumbakonam city. While Kumbakonam has been a temple city for centuries, Swamimalai flourished as the place where the idols were made for prayer.

The bronze icon crafts reached their peak around the 9th to 13th century AD under the rule of the Chola dynasty which patronized the craft greatly.

Traditional usage: The craftsmen of the ‘Sthapathi’ tribe craft bronze idols that are installed in temples and prayed to. The artisans follow the divine Hindu scripture of ‘Shilpa Shastra’ which is a book on crafting idols and temple architecture, making them masters of this niche.

Contemporary influence: These bronze idols have a great international demand to date with around 60% of the pieces being exported to countries like the US, UK, Australia, South Africa, Malaysia, and Thailand. The idols are exported to be installed in Hindu temples around the world.

75% of these international exports are done towards the Tamil community living abroad since bronze idols are a more culturally important phenomenon for them.

Crafting method: The lost wax technique is used to forge these idols where a mold is first created for the design. A dummy clay model is first made around which the mold is created. Then, the clay model is melted and taken out so that molten bronze can be filled in the hollow mold. Through this precise casting process, the idols are crafted in perfect dimensions.

The ‘shilpi shastra’ that the artisans follow gives precise dimensions for facial features and body measurements while crafting idols. The artisans strictly follow these instructions and hence make figurines that are believed truly godly in the old-world crafting school.

Raw materials: Bronze is the key metal for these idols which is also considered very important while installing deities in temples in the south.

⬝ Arani silk

GI issued on 28th March, 2008

Origins: The hand-loomed silk sarees of Arani can be traced back to the ‘Saurashtrans’ community in the western regions of India. The artisans of the community were celebrated as magicians when it came to working with cotton and were highly skilled in every stage of textile craft including stitching, dyeing, and embroidery among others.

The tribe however had to relocate due to endangerment concerns during war years. As they started migrating from 1000 AD, a part of them wound up in the town of Arni, in Tamil Nadu. They readily adapted to the resources in the village and its very own local craft variation, leading to a completely new style of hand-loomed fabrics known as Arani silk.

Traditional usage: Traditional silk sarees are one of the most prevalent articles of clothing made from this craft. Being an integral part of women’s fashion in South India this choice was a no-brainer. The sarees are conventionally hand-loomed in solid colors while the borders were woven with golden zari threads. This pattern became a standard application among Arani silk sarees.

Contemporary influence: These sarees have started to take inspiration from its neighboring weaving town of Kancheevaram to experiment with a wider range of designs and colors instead of the conventional solid pattern. Other enhancements include a shift to powered looms from handlooms. Where dobby looms were traditionally used, the process was sped up by using jacquard cards and automating the process.

Crafting method: The silk yarns are first washed and colored in a boiling solution using vegetable dyes. The yarns are then placed in the weft and warp of the fabric and produced using a dobby variety. The fabric can be woven in both frame and pit looms.

Raw materials: Mulberry silk is used for weaving the fabric which makes the saree extremely lightweight. The zari borders are woven using a golden yarn.

Lesser-known GI handicrafts

⬝ Pattamadai Pai

GI issued on 4th March, 2013

Origins: Pattampadai Pai translates to ‘The mats of the Pattampadai village.’ These mats are made of Korai grass and are known for their thinness despite being made of plant fiber.

These mats were first made 100 years ago by the Muslim community of Pattamadai. Rumored stories say that it was invented by Hassan Bawa Labbai who discovered that soaked grass can split up to 120 counts while normal mats could only split up to 30 to 40 counts.

Traditional usage: These mats were originally gifted around as novelty offerings that commemorate key occasions and festivities. It used to be gifted to brides and grooms on their wedding with their names and wedding dates inscribed.

Contemporary influence: The mats today are internationally celebrated as eco-friendly alternatives. They have a good global demand and are now produced on powered machines to reduce time and maximize production. They are known for their quality and durability and were even gifted to Queen Elizabeth and Queen Victoria during the British regime.

Crafting method: The korai grass for the mats is first collected and soaked in running water to rot. Once soaked, the central pith is scraped and the stems are split. The grass is soaked and split more times based on how thin the mat needs to be. After the strands are properly dried, they are woven into mats and dyed according to the desired palette.

Raw materials: Korai grass used for weaving enables the production of extremely thin mats making the key material for Pattamadai Pai.

Conclusion

With a lot of ethnic ground and communities having their own kind of regional craft that hasn’t been given a GI tag yet, the south promises to keep surprising with more stories taking center stage in years to come. But for now, these represent the best of the South by rather standing the test of time or with the help of conservationists who are just not ready to let them go!

Stay tuned for Qalara’s upcoming blogs, we will embark on similar journeys to discover more of India’s handicrafts, each with its unique tale of craftsmanship and artistic marvels.

~ Written by Dhanush Dandu

Leave a Reply