Crafting legacy: GI handicrafts from South India (II)

e had you traversing the rich artisanal lanes of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana in the last segment of the GI handicrafts series. Adding 2 more stops to our South Indian expedition, let us guide you through the regions of Karnataka and Kerala where we shall dissect some more heritage handicrafts that have been conferred with the GI handicrafts tag.

Table of contents:

Karnataka

Popular GI handicrafts

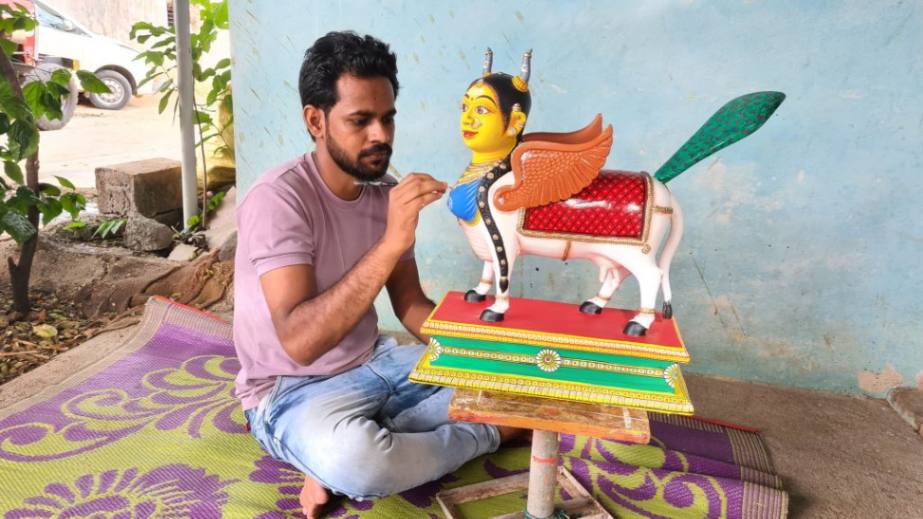

⬝ Kinhal toys

GI issued on 6th January, 2012

Origins: The toys came to be around the 15-16th centuries when the town of Kinhal was under the rule of the Vijayanagara empire. During that era, the Vijayanagara rulers invited artisans from across the Indian region to come to its capital city Hampi, which was not far away from Kinhal.

Artisans who settled there carved a unique style over time based on local resources and collective ability. These wooden craftworks came to be known as the Kinhal toys! Wealthy princes showed great interest in these toys and regularly bought them. Kinhal gradually became a flourishing center of such crafts.

Traditional usage: The immigrant artisans mainly worked in temples and palaces, creating murals and majestic wooden sculptures. The astounding works on temples and heritage sites in Hampi still owe their beauty to the Kinhal artisans.

Contemporary usage: Kinhal has struggled for its place in a world that has advanced to mass-manufactured purchases. The ‘Chitragar’ community that makes these crafts is down to 67 families out of which only half actively practice the craft.

Individual craftsmen have started to make efforts to adapt and have taken their works on social media to gradually develop a presence. A GI tag to prevent knockoffs and retain exclusivity is also a good boost in the right direction.

Crafting process: Kinhal toys are made using a special kind of wood that is light and soft. The wood is first procured and processed, ready to carve. The design of the model (typically a deity, flora, or fauna) is first drawn on a wall with charcoal. The artisans chisel an outline model from the wood first. If the figurine is very big, different parts are chiseled separately and joined together using a natural paste formed by mixing tamarind seeds and peddle paste. This gum-like paste is also used to emboss patterns on the figurine. The artisans then carve details on the toy, like expressions, and narrow outlines.

Once done, the figurine is completely covered in white paint, made from chalk powder. It is then painted, using the craft’s most prevalent colors, red, blue, yellow, and green. Gold and silver are also two colors produced by melting metal pieces. This method of making those two colors is known as the ‘Lajwara’ method.

Raw materials: The wood used to make the toys is called the ‘Ponki marra’ tree which exclusively grows around the Kinhal region. It is specially harvested for crafting and is inclusive to the process making the craft highly region-specific.

⬝ Kasuti embroidery

GI issued on 30th January, 2006

Origins: Kasuti, in the native language of Karnataka, is a fusion of two words. ‘Kai,’ meaning hand, and ‘suti/suttu,’ meaning warp/weave, loosely translating to ‘woven by hand.’ This folk embroidery craft is believed to have originated in the northern part of Karnataka back in the 7th century AD. Its design style involves the use of geometric lines and extensively has religious and cultural motifs associated with Hindu temples. These include lotus flowers, parrots, swans, palanquins, chariots, elephants, bulls, deers, etc.

Around the 17th century, the craft truly flourished under the Mysore kingdom. At that time, women thrived as artisans because they were socially expected to be skilled in over 64 art forms, including Kasuti. Practicing this embroidery as vocational home science, mothers generationally passed it down to their daughters, making it a very inclusive art of the culture of Karnataka.

Traditional usage: Kasuti embroidery work was extensively used to adorn sarees and blouses, because of which the craft spread across the Karnataka state rapidly. The culturally rooted designs were a perfect addition to ethnic wear like sarees.

Contemporary influence: Like a lot of traditional crafts, Kasuti has also suffered from poor patronage, was rendered time-consuming and impractical in today’s fast-paced and commercialized world.

While some skill development hubs and institutions have stopped teaching this craft for the same reason, other conservation-centered organizations are helping set up cooperative societies for women where they can learn and practice Kasuti embroidery, earning a living out of it.

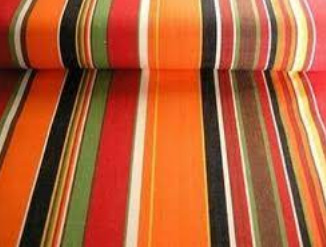

Crafting process: Kasuti embroidery is done by counting the weft and warp threads on the fabric. Hence, it requires patience and extremely skilled artisans. It is done only with steel needles and is stitched without any knots, by which the embroidery remains flat and even on both sides of the fabric. The stitches are usually in vertical, horizontal, or diagonal patterns which also explain the geometric lines design style. The fabric is usually in purple, crimson, black, red, green, and orange colors. The embroidery stitch is also done in multiple colors to make the design more vibrant.

Raw materials: The embroidery is usually done in silk fabrics like georgette or chiffon. The cotton threads used for embroidery were originally extracted from the raw fabric. Now, they are acquired from the Mysore region in Karnataka. These single-strand threads called ‘Kohinoor’ and ‘Anchor’ are deemed perfect to practice the Kasuti craft.

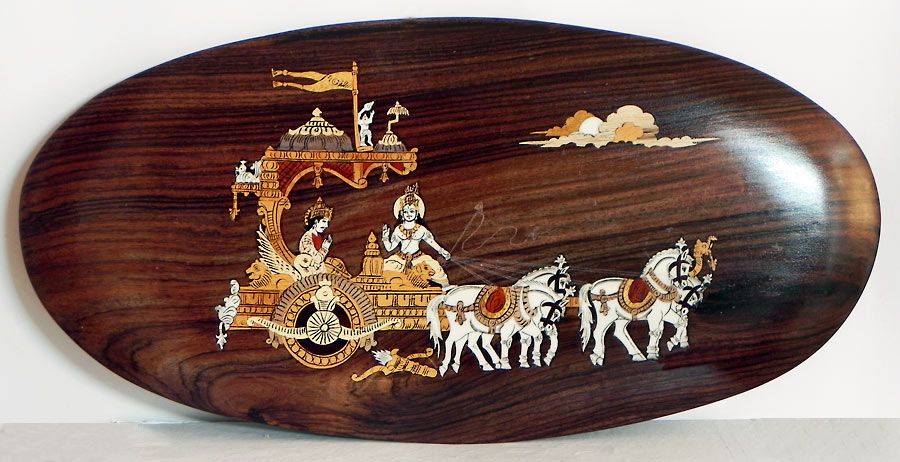

⬝ Mysore rosewood inlay

GI issued on 30th January, 2006

Origins: Rosewood inlay work started in the 17th century Mysore. The abundance of Rosewood in the Mysore region led the artisans to use the material for crafting. Soon they got creative with the material and experimented with different shades of wood, ivory, MOP, gold, horn, bone, etc., inlaying them on the wood to create beautiful designs. The resultant crafts were so visually stunning that they received royal patronage from the rulers of Mysore.

Traditional usage: Beautiful inlay work would be done on all sorts of wooden offerings including decoratives, tables, side tables, chairs, and all kinds of furniture. The inlay work extensively touts designs that reflect the local heritage of Mysore and the beauty of its local Dusherra festival. These designs are that of deities, dancers, celebrations, rural festivities, flora, and fauna.

Contemporary influence: Currently, only 4000 artisan families are still practicing this craft. As the younger generations have started swaying to different interests and the price of rosewood is on the rise, the number of artisans has started to diminish. GI tag, exclusivity, and global interest in these exotic crafts have been a lifesaver.

Crafting process: The inlay process starts with thoroughly smoothening the surface of the rosewood. The intended design is traced on the surface and etched properly. Then different materials based on preference are inlaid into these grooves, completing the process. The design pattern is quite repetitive and gives a beautiful color contrast to brown wood when white inlay materials like MOP and bone are used.

Raw materials: Rosewood available in the Mysore region is the key material, justifying the crafts GI tag as well. Ivory was a very prominent inlay material when the craft started. Now, keeping in mind the need to conserve elephants, hydrogen peroxide is used instead. Other prominent choices are gold, bone, horn, and MOP.

⬝ Channapatna toys & dolls

GI issued on 30th January, 2006

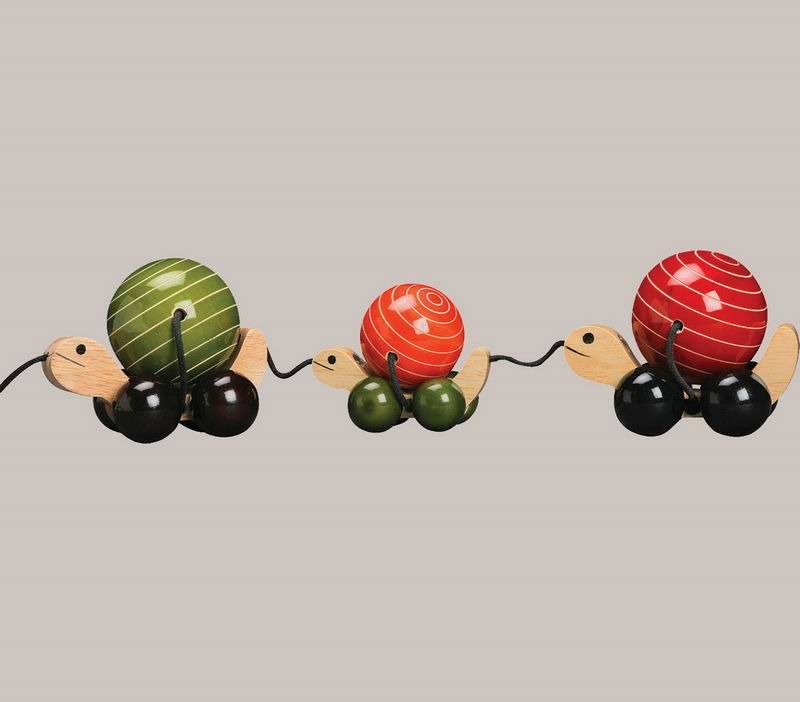

Origins: The Channapatna town, from which this wooden toy-making craft originates is lovingly called ‘Gombegala ooru,’ or the ‘Toy town’ in the native Kannada language. Large-scale patronage of the Channapatna toys can first be traced back to the 18th century Mysore kingdom when its emperor Tipu Sultan was blown away by this intricate woodwork. He invited Persian artisans to Mysore and urged them to train the local artisans in the art of lacquerware. What evolved out of this beautiful exchange of ideas are the famous Channapatna toys. They are made of softwood, have a smooth texture, do not have sharp edges at all, and are painted with vibrant, natural, and non-toxic colors. What’s more, the toys look absolutely stunning!

Traditional usage: Before receiving royal patronage in the 28th century, the toys were predominantly used as gifting articles during the Hindu festival of Dusshera. While the core artistic style of bright wooden, natural-colored toys remained, the craft underwent a lot of manufacturing-based evolution.

The 19th century saw the influence of Japanese doll-making techniques to reduce time and opened up new possibilities for design. This was introduced by a local craftsman named ‘Bavas Miyan.’ The 20th century again saw the introduction of the wooden lathe for toy making which helped with faster production and newer design possibilities.

Contemporary influence: Despite having a bad patch for over a decade, Channapatna toys are on the rise now. While government organizations and NGOs have also been trying to promote the practice of the craft by training rural artisans, a demand for sustainable and eco-friendly products started growing. This led the Channapatna toys to receive the limelight as a traditional craft with an environmentally conscious ethos.

The artisans have also been readily playing the game and adapting to contemporary trends to give the toys a more global appeal. Despite this, the artisans’ community still makes room for traditional crafting in the creations.

Crafting process: The wood is first worked up on using chisels, knives, and sandpaper. Once the artisans skillfully achieve the desired design, it is polished to make the surface extremely smooth. Then, the toys are coated with lacquer, acting as a sealant, protecting the wood from damage, and increasing its durability. Then comes the coloring which is usually a very bright and vibrant palette that stands out. The process of hand painting is also very intricate and the artisans try to get the narrow outlines and details just right.

Raw materials: The wood used to make the toys is known as ‘aale maara’ or ivory wood. It is preferred for its smooth texture and easily sculptable characteristics. The colors used are completely natural and are extracted from flowers, fruits, trees, and vegetables.

Also read: Qalara’s toys hit the famous Hamleys stores

Lesser-known GI handicrafts

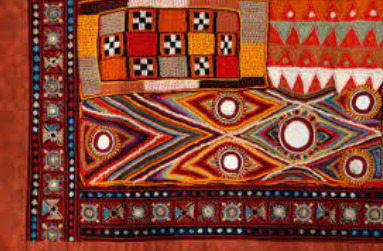

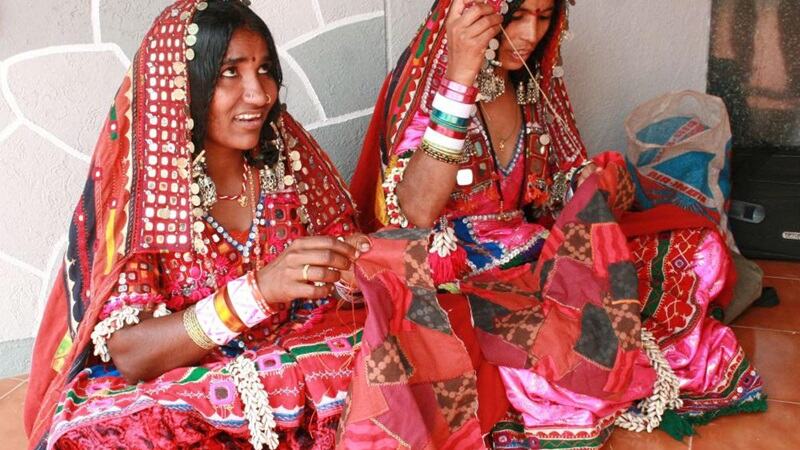

⬝ Sandur Lambani embroidery

GI issued on 3rd September, 2010

Origins: This craft comes from the ‘Lambani’ tribe of India which is a semi-nomadic tribe known to be wanderers. They originate from the northern part of India and were used by the Mughal dynasty in their military to help transport supplies and weapons to the southern part of India, which they were trying to conquer. This brought the Lamabnis to the south.

However, as a new era of the British Raj came to be, the Lambani faced several difficulties due to changed laws, incomplete roadways, and intense criticism of their nomadic lifestyle. This pushed them to split up and settle down in ‘thandas’ (villages) across the south and central Indian regions. Post-settlement, while the men struggled to find work, the women at home chose to create clothing and accessories out of the materials and embellishments they could find. A bohemian approach to design, merged with a very Indian inclination to employ a vibrant color palette gave birth to this new kind of embroidery.

Traditional usage: The very first usage of this design was applied to traditional sarees and handbags. It was made of readily available scraps like mirrors, leather patches, applique scraps, beads, quilted stitches, and so on. Hand-embroidered fashion has since become an integral piece of clothing for the tribe.

Contemporary influence: Lambani embroidery has received a lot of acclaim lately with international markets showing lots of interest. With an unapologetically bright and bohemian theme, it stands out on most shelves. Since the craft received its GI tag in 2010, the demand has only increased which has also led to the tribal folk being able to achieve better living standards.

Crafting process: The process starts with dyeing the cloth on which the embroidery is supposed to be done. The pattern and color palette are pre-decided, based on which the cloth is colored. After this, the stitching process begins. Sandur Lambani embroidery has 14 different kinds of stitch variations, each giving a different pattern.

The patterns are usually geometric and have various shapes like triangles, circles, rectangles, parallel lines, and so on. Applique work is also a part of this where different color patches are stitched to the fabric. Then comes the embellishing which is majorly done with mirrors, coins, and shells of different shapes and textures.

Raw materials: The cloth and the threads used for stitching are simple cotton. Mirrors, coins, shells, and beads are a part of their regular embellishments. This craft relies less on material exclusivity and more on pattern and design match application.

⬝ Navalgund durries

GI issued on 28th March, 2008

Origins: Navalgund dhurries or rugs originate from the city of Bijapur and not the town of Navalgund. It was practiced by the women of the ‘Sheikh Sayed’ community. These skilled rug weavers saw their livelihood in the art and respected it beyond just a source of income.

In the 16th century, when two prominent Southern empires, the Vijayanagara Kingdom and the Deccan Sultanate, were at war, these weavers saw it as a threat to their craft, being unable to practice it freely. This led them to migrate to the hill town of Navalgund. Translating to ‘The hill of peacocks,’ Navalgund came with its own kind of beauty and the weavers readily imbibed it in their craft, so much so that the peacock is a very prominent motif in their rug designs today. This way, a town, and a community collectively gave the best they could offer, to produce a timeless craft.

Traditional usage: Navalgud dhurrie has been an exclusive rug-making craft. They are made in different sizes, catering to various floor covering needs including prayer mats as well. Its salient features are a geometric design style, and motifs including peacocks, dice game boards, and arches. It chooses a vibrant color palette sticking to a very bright Indian design sensibility.

Contemporary influence: In 1988, weaving centers were established in Navalgund where women (not just from the community) could practice the craft. The craft kept going but these women worked in very bad conditions with no health plans, insurance, or even basic sanitation facilities like restrooms.

The spirit of these weavers took a major beating during the pandemic when coming to the centers was not an option. While the craft was traditionally practiced at home, modern times meant smaller living spaces and rented houses where a handweaving setup was tricky. This led to a sizable decline in the number of people practicing the craft.

Crafting process: The rugs are woven on a vertical loom pit known as the ‘khadav magga.’ Accordingly, the weaving and design are weft-dominant, while the warp is usually just a white yarn. Loom has a precise calculation in the weaving pattern but the artisans work with no reference to design and simply rely on skill and experience, muscle memory, and a lot of improvisation. Another piece of equipment called ‘tibni’ is used to push the threads down. It is a pointed wooden stool. A ‘panja’ tool is used to push the thread down after every line to tighten the weave.

Raw materials: The fabric used to make the durrie is 100% cotton yarn. This, along with a completely non-mechanized process has also made the craft eco-friendly, producing negligible ecological footprint.

Kerala

Popular GI handicrafts

⬝ Cannanore home furnishings

GI issued on 4th September, 2009

Origins: The geographical tag, Cannanore, of this craft, is the former name of the coastal city of Kannur, in the Kerala state. Located on the eastern coast of the Indian subcontinent, Cannanore essentially became the world’s sea gateway to India. With abundant natural resources in its fertile region, it immediately transformed into a global trading hub. This pushed the German Christian missionary society, ‘The Basel Mission,’ to start a handloom station there in 1852. The skill and technique they brought combined with the abundance of resources, local craftsmanship, and design aesthetics brought a new style of woven home furnishings known for their unmatched quality, design, and durability.

Traditional usage: Even at the start of this weaving practice, the offerings included a whole range of home furnishings including bedspreads, curtains, pillowcases, tablecloths, and other such home linen. As a homegrown craft, it held high significance in the cultural fabric of Kerala state, often used as a very crucial offering in festivals and religious occasions.

Contemporary influence: Eventually, after a few years of ‘The Basel Mission’ era, authentic techniques took a dip with a lot of the stations shifting to power looming. Yet, some artisans continued and even set up a looming unit to work out of their homes.

The 1960s though saw a major shift in demand with global audiences turning towards this beautiful, local, and eco-friendly craft. Artisans have also readily taken on this challenge and constantly try to adapt to contemporary trends to show their very native craft in a newer, exciting light.

Crafting method: Handlooming is the crux of this craft. Handloomed fabrics are beautifully dyed using naturally extracted colors from trees, flowers and vegetables. The fabric’s distinctive quality is its visual freshness almost making the shades feel alive. The color palette is also very dynamic and vibrant. The patterns and designs typically worked on the fabric are themes inspired by local folklore, flora, and fauna, all of which personalize this technique even more.

Raw materials: The fabric used is often between cotton, silk, and jute based on the product’s use cases. Either way, everything is locally sourced from its highly resourceful region. As this naturally eco-conscious craft saw the world’s inclination towards sustainable living, it went all the way to create global offerings that represent an eco-friendly lifestyle.

⬝ Brass broidered coconut shell crafts

GI issued on 10th July, 2008

Origins: Coconut crafts with an exotic brass broidery in its design is a technique exclusive to the tropical coastal region of Kerala. The exact origin of the craft tends to become unclear. This is because artisans around the world, living in areas with abundant coconuts, naturally gravitated toward this shell carving craft. So did the ones from Kerala. This is also why the region has two different centers of production for these crafts, in the cities of Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode.

What differentiates the story here is that their high level of skill in working with these coconuts attracted international trade and merchants from the Middle East around the 16th century. These merchants and migrants formed settlements in Kerala and influenced the shell crafts. From their wood carving skills and design aesthetics to product use cases, they influenced the local crafting scene.

Traditional usage: Because of the high durability of the coconut shell, it was used to create stunning decorative and fancy kitchenware that can last for even 100 years! This range of products includes cups, boxes, spoons, snuff boxes, flower vases, nut bowls, and powder boxes among others. Middle Eastern influence has also created the very famous ‘Malabar hookah’ which is crafted out of coconut shells and brass detail.

Contemporary influence: The exotic coconut craft industry has been thriving in the contemporary market that has been longing for eco-conscious and sustainable substitutes for modern plastic. This is a striking tourist attraction and also has an international market otherwise.

Crafting method: Crafting a coconut shell is a high-precision, high-skill task that these artisans have perfected. Once the design is sketched for the shell, it is very carefully cut. Blades, files, hammers, and chisels were extensively used for this at the beginning. But a lot of the process is now aided by powered machines. Once cut, it is given a good finish and polished by sanding and buffing the product. Tools like adhesives, wood polish, and gloss top coats are used for the same.

The brass broidery on the shell is done using the lost wax process which is a precision casting technique that gives brass an intricate design shape on the shell. The vintage sheens of brass along with the raw browns of coconut give a beautiful contrast to the product, making the design one of a kind!

Raw materials: Coconut shells are the star of the show here, basing the whole process on this amazing material! Brass metal accentuates the coconut’s beauty with its shades.

⬝ Alleppey Coir

GI issued on 16th May, 2007

Origins: The origin of the Alleppy coir can be credited to the problem of abundance. The city of Alleppy is known for having the largest backwaters in the Kerala region, even being referred to, as ‘The Venice of the East.’ The conditions of the area are so perfect for the cultivation of coconuts that a number of use cases are fulfilled by centering manufacturing around this resource.

One such idea was using coconut husks as the coir fiber to create sturdy ropes and nets. Like this, the coir industry emerged in Alleppy for the first time in India in 1857. The factory was set up by an Irish-American entrepreneur by the name of James Darragh. Since then, Alleppy has become the cradle of India’s coir industry.

Traditional usage: Coir is essentially used to manufacture ropes. Locally, the major population of Alleppy was fishermen. So, fishing nets and related equipment have been one of its earliest uses. Along with this, it was widely used for agriculture and construction. Ultimately, coir ropes have now become a part of our daily life either based on necessity or aesthetics rendering the rope use case, ‘always relevant!’

Contemporary influence: Over coir manufactured from other areas, Alleppy coir became famous for its strength, color, durability, flexibility, and overall quality of the material which even led to its very own GI tag. The global market also acknowledges this quality and shows the product the same kind of respect that it deserves. Alleppy coir, hence stays high in demand today and is expected to nearly 104 countries from around 250 exporters!

Crafting method: Mature coconut husk fiber is first collected and soaked in salt water for a period of 6 to 10 months. This process is called retting. This loosens the thick fibers, makes them flexible, and even prevents the material from rotting. After this process, the fiber becomes ready for spinning. It is sun-dried and spun along a traditional hand machine called a ‘charkha.’ This creates a yarn which is then woven into mats or fashioned into sturdy ropes.

Raw material: Coir comes from the outer husk layer of the Coconut which is essentially the only material that goes into creating a coir.

Lesser-known GI handicrafts

⬝ Maddalam of Palakkad

GI issued on 22nd April, 2008

Origins: A maddalam is a traditional Indian leather percussion musical instrument that is known to emit the sacred Hindu sound of ‘Om.’ While it was invented around the 13th century, the expert craftsmanship of the artisans of Palakkad city made it unique.

Palakkad has been home to a whole village of craftsmen specialized in making percussion instruments. These craftsmen are known for their expertise in crafting the instruments, so much so that traditional musicians from around the world go there to tune their instruments. With a 200-year-old legacy, the craftsmen of Palakkad have proved that they are at the pinnacle of their skill, eventually producing Maddalams with a make so unmatched that they received their own GI tag.

Traditional usage: This product is a fully functional musical instrument used to produce music. Maddalam is an important instrument used during traditional Indian dances like Kathakali. In mythology, it is known to be played for the dance of the Hindu god Shiva.

Contemporary influence: In Palakkad, there are around 74 families that work on crafting instruments like these Maddalams. It is an extensive, time-consuming process and the artisan’s community considers it a divine practice. This is why the instruments are not commercially sold to customers or agents in a mass-produced fashion (which would have been an easier way to make more money for them).

Each piece needs to a pre-ordered while the craftsmen put their heart and soul into it, customizing it according to the customer’s requirements.

Crafting method: The head of the head of the maddalam is made using animal leather. It is stretched tightly and bound using wooden stripes at the end. A paste of boiled rice and charcoal, called ‘choriduka’ is used to bind these both.

The wooden structure in between needs to be hollow from the inside and was originally hand-cut by the artisans using tools like chisels and hammers. While powered machines sped up the process, a lot of it needs manual handwork.

Raw material: The wood used is usually among types like jackwood, chempakkam, and karungally. The other material is animal leather that is carefully treated which will essentially be the main source of sound.

⬝ Aranmula Kannadi

GI issued on 19th September, 2005

Origins: A ‘Kannadi’ is a traditional Indian metal mirror that is crafted using a special reflective alloy made of copper and tin. The ‘kannadi’ is known for its superior and distortion-free reflection compared to a normal mirror, often dubbed by the locals as ‘a mirror that shows you your truest self.’ It was invented and practiced to date in the town of Aranmula.

It originated a few centuries ago when 8 families of temple art & crafts experts were brought here from Thirunalaveni city to undertake some work in the famous Krishna temple in Aranmula.

While working with bronze to make the crown of the deity, one of the artisans came across a very interesting alloy that had extensive reflective qualities. Then, the alloy was worked on and experimented with to come up with an apt composition to create an absolutely reflective mirror. This gave birth to a medieval marvel that was a fully functional metal mirror long before glass mirrors came into the market.

Traditional usage: Kannadi mirrors are exclusively crafted by the artisans of Aranmula and very important motif in the Hindu culture in the Kerala region. A kannadi is one of the 8 auspicious items that are arranged on important occasions like weddings and festivals. Keeping a kannadi at home is also believed to bring luck, wealth, and prosperity. This makes it an exotic gift piece that is a symbol of the beliefs of the people in Aranmula.

Contemporary influence: The families of Aranumula, crafting the Kannadi mirror have kept its production technique a close guarded secret that only passes down from generation to generation.

While normal mirrors reflect from the rear end of their glass and leave a small distortion gap between the actual object and the visual, Kannadi reflects from the front end of the glass giving a precise visual without error. This makes the kannadi mirror far superior to the ones we use daily.

The alloy composition that enables this characteristic is a trade secret that the artisans closely hold on to. Many other manufacturers have tried to come close to their own compositions because of which the government issued these kannadis a GI tag safeguarding the unmatched quality of the Aranmula craftsmanship.

While the demand for this product took a small dip initially, the government of Kerala has been proactive in its revival, declaring Aranmula a model tourism village and attracting the world to tell the very interesting story of this legendary craft.

Crafting method: The secret metal alloy mix is first formed into a concave mirror and hand-polished to perfection. To get the right reflective property, each piece is individually polished for 2 to 3 days before an authentic kannadi is ready. The process is completely eco-friendly and ensures minimal waste, with craftsmen utilizing leftover alloy in production as well.

Raw material: The metal alloy for the mirror predominantly consists of copper and tin. Other components and the exact composition of the alloy are unknown to outsiders and are kept with the crafting community of Aranmula.

Conclusion

From the majestic south-Indian states of Karnataka and Kerala, we have trailed across the remarkable handicraft techniques that have withstood the test of time and emerged vital to the art-history of India. Vouching their authenticity and heritage-value, the Indian government bestowed them with the GI tag that grants these age-old methods the recognition they deserve. How many of these did you already know about? Let us know in the comments section below and hang around to check out the final segment of this series soon!

~ Written by Dhanush Dandu

Leave a Reply