I

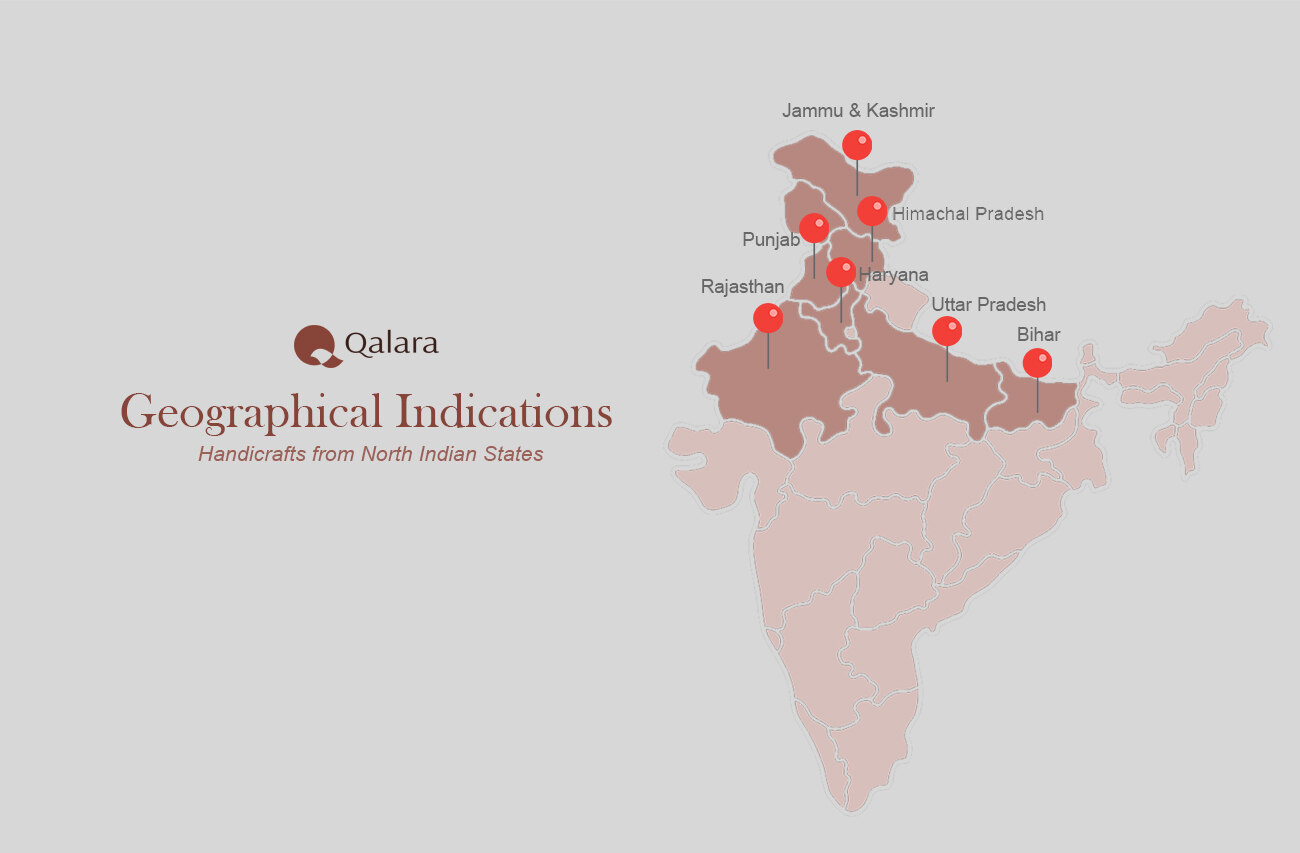

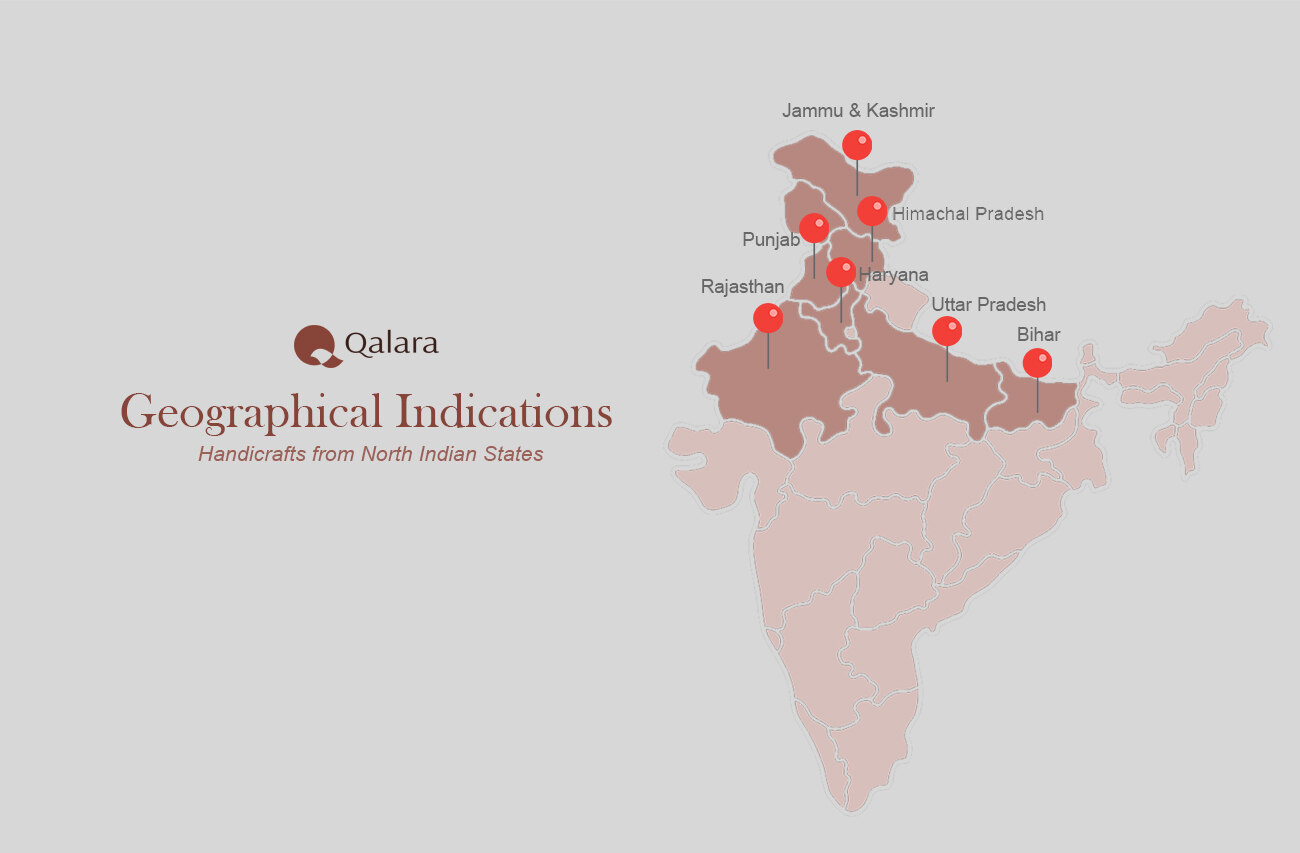

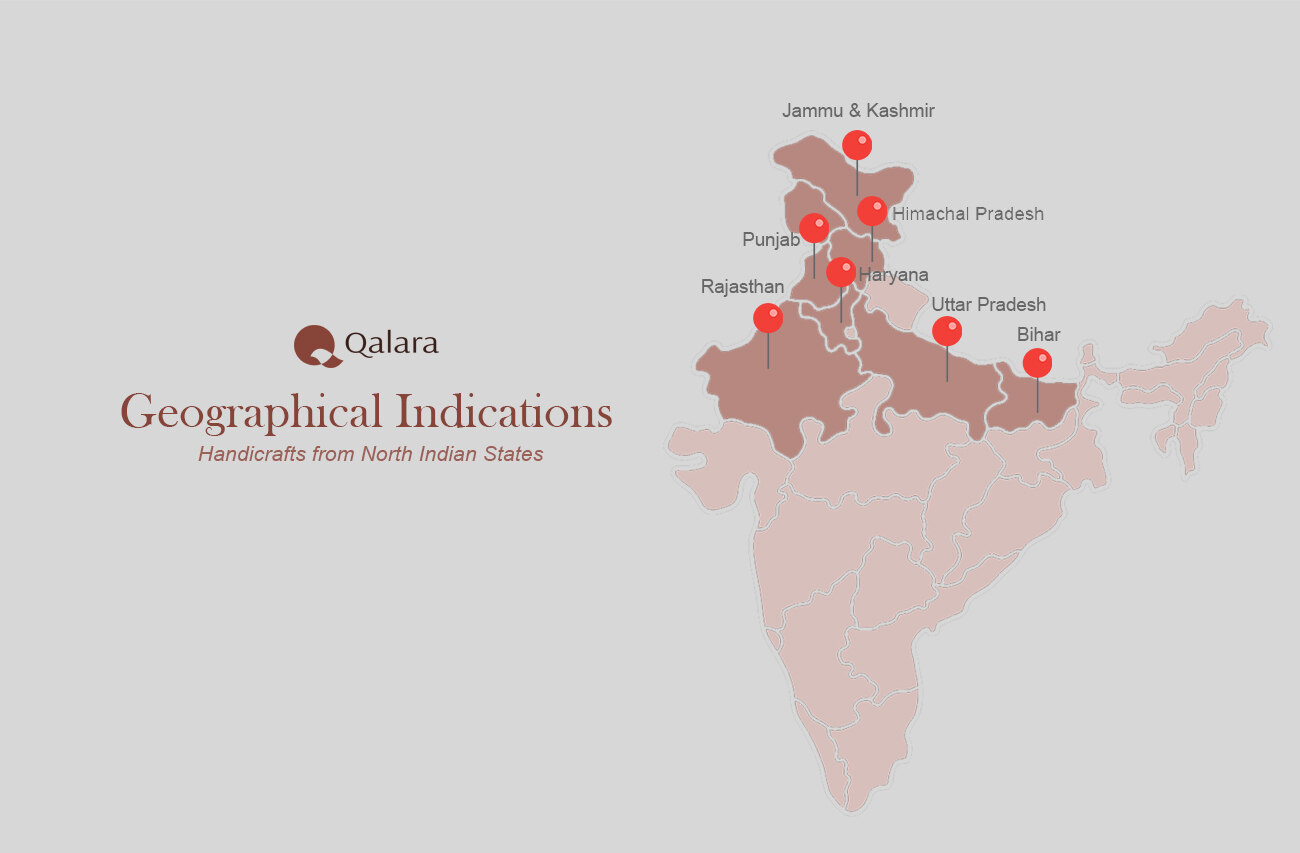

ndia, a land steeped in history, culture, and artistic heritage, is a tapestry of vivid colors, intricate designs, and exceptional craftsmanship. Its rich cultural mosaic has woven a tapestry of artistic brilliance over millennia. Among its many cultural treasures, Indian handicrafts stand as testament to the nation's enduring commitment to creative expression.

E-Startup India

I really appreciate the initiative you have taken to provide information to general public, this will help us a lot… Knowledge is a very powerful tool and will help our audience more… We have also shared some detailed information on the topic, Please have a look on our blogs.